Week 42—“Although it’s always crowded | You still can find some room | For broken-hearted lovers |To cry there in the gloom” (“Heartbreak Hotel” (Mae Boren Axton and Tommy Durden (1955)))

The above photograph of the title page of a sixteen-page pamphlet by the famous illustrator George Cruikshank, published in 1851, is © Trustees of the British Museum. Fortunately, the Admiral didn’t require the hints in the pamphlet to protect himself against Magdalen; he had Mazey.

When Mazey discovers Magdalen with Noel’s letter to the Admiral in her hand, he says to her, “You young jade, you’ve committed burglary—that’s what you’ve done. His honor the admiral’s keys stolen; his honor the admiral’s desk ransacked; and his honor the admiral’s private letters broke open. Burglary! Burglary!”

Burglary was originally a crime created by the judges (in other words, a common law crime), as opposed to one created by the legislature (in other words, a statutory crime).

As created by the judges, the crime of burglary consisted, generally speaking, of the breaking and entering by a person of the dwelling house of another person at night with the intent to commit a felony in that house. The felony very often intended to be committed was larceny, but, whatever the felony intended to be committed, it didn’t matter whether that felony was afterwards committed or not. The crime of burglary was complete once the offender had broken and entered the house at night with the requisite intent, regardless of what happened afterwards.

For Mazey to claim, as he appears to have been doing, that Magdalen had committed burglary because she’d stolen the Admiral’s keys, ransacked his desk and opened his private letters was, as appears from the above definition of the crime, manifestly wrong.

That’s not to say, however, that Magdalen hadn’t committed burglary for reasons other than those put forward by Mazey.

Although the above statement of the elements of the crime of burglary sufficed for most purposes, factual situations arose that led to its massaging by the judges, including the factual situation of a household containing a servant, in which case the focus could shift from the breaking of an exterior part of the house (usually a door or window) and consequent entry into the house to the breaking of an inner door of the house and consequent entry into a part of the house.

Here’s an extract from a leading English criminal law textbook current at the date that our story has now reached (Russell On Crimes (third edition; 1843), at page 794; I’ve kept the peculiar punctuation intact):

… in the case of a servant opening a door of his master’s house for a felonious purpose, … it seems to have been considered, that the question whether such act will amount to a breaking must depend on the point, whether the door might have been opened by the servant in the course of his trust and employment. Thus, it is said, that if a servant unlatch a door, or turn a key in a door of his master’s house, and steal property out of the room; such opening of the door, being within his trust, is not a breaking: but that if a servant break open a door, … (as a closet, study, or counting house,) and steal goods, such opening, not being within his trust, will amount to a breaking of the house, … within the law of burglary.

Although the editor of the textbook acknowledged that a distinction between unlatching or turning a key in an inner door, on the one hand, and breaking open an inner door, on the other, had been made by an earlier author, he expressed doubt as to its correctness and referred by way of refutation of it to a case “where a servant who unlatched the stair-foot door and went with a hatchet to kill his master, was held guilty of burglary.” (Obviously, the servant didn’t succeed or else he’d have been charged with murder, rather than burglary.)

(It’s possible, though not probable, that the distinction that had earlier been made between a servant’s opening a closed inner door by the usual means and opening it by unusual means had been made only because of the severity at the time of the punishment if one were convicted of burglary. (However, if that had been the reason, then why had no similar distinction been made regarding the opening of a house’s exterior doors? In that case, opening a door by the usual means was “breaking”, just as much was opening it by unusual means.))

If the opening by the usual means by a servant at night of a closed door to a room in the house in which he or she was employed and the servant’s consequent entry into that room with the intent of stealing something in that room amounted to burglary, then Magdalen had committed burglary, even if she didn’t in the result steal anything while in that room pursuant to that entry. She’d committed it at least once, on the night that she ultimately found Noel’s letter, when, on the first occasion, “She reached the door of the first of the eastern rooms—opened it—and ran in.”

(Incidentally, the fact that Magdalen didn’t know when she entered that room on that occasion whether the letter that she hoped to find was in it doesn’t mean that she didn’t intend, so far as the crime of burglary was concerned, to commit larceny in that room. An intent to steal a thing that she wanted, conditional on its being present in the room that she broke and entered at night, sufficed for the purpose.)

*****

Yet again, we have some information about the cart situation in the Admiral’s household. In earlier instalments we’d had reference to his spring-cart and to his dog-cart. In this week’s instalment, we hear of his “light cart”, used to assist Magdalen to make her escape, and of the fact that Mazey had induced the driver of it to “put a leather-cushion on the cart-seat for his fellow-traveller.”

Does this reference to his light cart mean that the Admiral had another cart additional to those already mentioned in earlier instalments?

I think that it does. This cart was being used to go to market day at Ossory. It seems likely to have been devoted to the carriage of goods, rather than persons, in which case George is unlikely to have used it. It therefore isn’t the same cart as the dog-cart. Further, a carriage devoted to the carriage of goods is unlikely to have been sprung. It therefore isn’t the same cart as the spring-cart.

*****

George writes to the Admiral from London on APR 03 1848 (though Collins doesn’t mention it, a Monday), telling the Admiral that he’s discovered that Norah and her employers, the Tyrrels, have gone to Paris and adding, “I mean to cross the Channel, after them, by the mail [train] to-night.”

George (and the mail) would have reached the English south coast from London by train, switched to a boat for the Channel crossing and then switched to another train to travel from the French north coast to Paris.

George seems to have been the first, but was by no means the last, character said plainly by Collins in his fiction to have travelled between London and Paris by the mail train.

In making his journey, George would be using a service offered by the South Eastern Railway (“the SER”), involving a boat crossing from Dover to Calais.

George Measom, The Official Illustrated Guide to the South Eastern Railway (1853) mentions, at pages vii-vii, that the SER “offers unusual facilities for persons visiting the Continent—for it is the shortest and most direct route to Paris”. According to him, among other SER trains, “[T]here is a night mail train, which, leaving London at 8.30 pm, reaches Dover at 11.15, in time for the [mail] packet [boat], and the train reaches Paris at 9 the following morning.”

Since George was proposing to travel on a Monday night, he would have had no difficulty in using the SER service just mentioned to reach Paris in twelve and a half hours. (A traveller proposing to travel on a Sunday night would have had a much longer journey, since that was the only night of the week on which the packet boats didn’t run.)

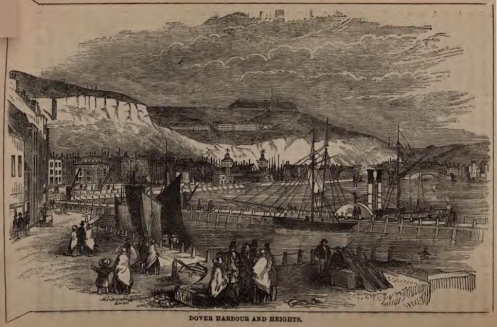

The above illustration, from around the date that our story had now reached, is from here. The steamer in the distance is similar to the one that George would have taken to cross the Channel.

Dickens was a frequent user of the mail train to Paris. In 1864 (by which time the mail train to Paris was being operated by the London Chatham & Dover Railway, rather than by the SER), he wrote in a letter (here),

My being on the Dover line [at Gad’s Hill], and my being very fond of France, occasion me to cross the Channel perpetually. Whenever I feel that I have worked too much, or am on the eve of overdoing it, and want a change, away I go by the mail-train, and turn up in Paris or anywhere else that suits my humour, next morning. So I come back as fresh as a daisy, and preserve as ruddy a face as though I never leant over a sheet of paper. When I retire from a literary life I think of setting up as a Channel pilot.

Years earlier, in 1851, he’d published an account of travelling from London to Paris on the SER, although not the mail train and not crossing the Channel from Dover to Calais, but rather crossing it from Folkestone to Boulogne, the SER’s preferred crossing: see this.

*****

If recollection serves me, we’ve had reference thus far in our story to two hotels, both imaginary, the Aldborough Hotel in Aldborough and Mussared’s Hotel in London.

After the failure of his Paris venture, our broken-hearted lover George writes to Miss Garth, inviting her to reply to him in care of Long’s Hotel, where he intends presumably to cry in the gloom. The context makes plain that George is referring to a Long’s Hotel in London.

I’ve earlier suggested that the reason why Collins used the two imaginary hotels that he did was because he wanted to involve the operators of them in the development of the story. Presumably, Collins had no need to involve in the development of the story the operator of the hotel at which George announced that he’d be staying and for that reason felt free on this occasion to put his character into a real-life hotel.

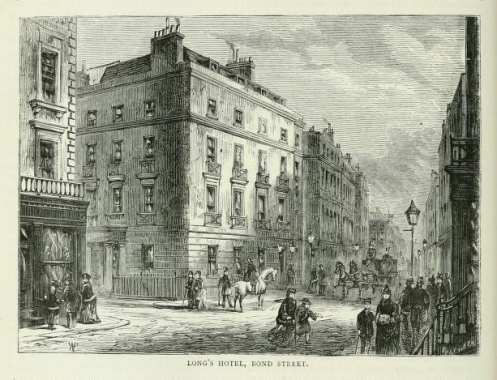

The above illustration (from here) is of Long’s Hotel, 16 New Bond Street, London, the hotel to which George was apparently referring. The hotel may have been established as early as 1687. Certainly, at the date that our story has now reached, it was operating in the building depicted in the above illustration. In 1887, the building illustrated was reconstructed and the hotel continued to operate in the reconstructed building until 1911, when it ceased business.

Collins’s 1862 reference to Long’s Hotel was certainly not the first reference to it in fiction. Limiting myself: to only the preceding twenty years or so; and to other leading Victorian writers of fiction, one can find the hotel mentioned in the fiction of: (1) Thackeray (the stories “Mr and Mrs Frank Berry” and “The Ravenswing” (first published separately in 1843; afterwards published as part of Men’s Wives (1852)): here and here respectively); (2) Dickens (the novel Dombey and Son (first published serially in 1846-8): here and here; and the story “To be Read at Dusk” (first published in The Keepsake (1852)): here); and (3) Trollope (the novel Dr Thorne (first published in 1858): here).

Perhaps the most famous of the numerous non-fictional literary references to Long’s had been made as long ago as 1825 and had referred to an event that had occurred ten years earlier. In an entry in his journal dated DEC 21 1825, Sir Walter Scott referred (here) to “odd associations” attending some meetings of his with his “old friend [Charles] Mathews, the comedian”. One of those meetings, wrote Scott, had been,

… in 1815, when John Scott of Gala and I were returning from France, and passed through London, when we brought Mathews down as far as Leamington. Poor Byron lunched, or rather made an early dinner, with us at Long’s, and a most brilliant day we had of it. I never saw Byron so full of fun, frolic, wit, and whim: he was as playful as a kitten. Well, I never saw him again.

Incidentally, according to Mrs Mathews (here), Mr Mathews, while on the road with Scott, wrote to her about that dinner, saying of Byron that he was the “handsomest man I ever saw”. How Byron would have enjoyed that, had he known!

(As it happens, Scott had earlier mentioned Long’s in his only novel with a nineteenth century setting, St Ronan’s Well (1824): here.)

As our read of No Name rapidly approaches its end, I’m wondering if another read-by-installment is being planned. I’ve much enjoyed this one.