Week 26—“Holy moley!”

The interjection that provides the title for this week’s post is of obscure meaning. It was popularised in America in the 1940s by the comic book hero Captain Marvel (see, for instance, this), but had been used earlier. Here it is as used in an 1892 novel written in Australia.

*****

This week’s instalment opens with Captain Wragge expressing to Magdalen the opinion that “the time ha[s] come for bringing Noel Vanstone, with the least possible delay, to the point of making a proposal.”

Implicit in that expression of opinion is the notion that the dealings thus far between Noel and Magdalen have been such that he can now quickly be persuaded to propose marriage to her.

A summary of those dealings follows.

Magdalen arrives in Aldborough on JUL 24 1847 and, although Noel sees her that evening as she and Wragge walk by Noel’s house, he does not then meet her.

On JUL 25, at some time shortly after 2 pm, Noel meets Magdalen for the first time, during a walk on the Crag Path. They are two of a party of four, the others being Wragge and Mrs Lecount. We aren’t told the length of time that the walk takes, but it seems that it couldn’t be more than an hour, judging from Collins’s treatment of what occurs. During the walk, Wragge seeks to distract Mrs Lecount, so that she won’t hear any of the conversation between Noel and Magdalen. Then, at 7 pm that evening, Wragge and Magdalen go to Noel’s house, where they stay till 10pm. Again, the party consists of the four walkers and again, Wragge seeks to distract Mrs Lecount.

On JUL 26, at 11 am, the four walkers of the previous day travel together by carriage to Dunwich, a trip that I’ve suggested in an earlier post probably took about two hours each way. While they’re there for some unspecified period of time, Wragge contrives to have Noel and Magdalen be alone together for nearly an hour. At some point on the trip back, Magdalen, at Wragge’s instance, feigns neuralgia, so as to end her participation in any conversation.

Three days then pass during which Noel doesn’t see Magdalen, the last of them being JUL 29, on which day Wragge expresses the opinion with which I began this section of my post.

We thus see that so far Noel has only ever been in Magdalen’s presence on two days, for about four hours on the first day and for somewhat more on the second day, for part of which latter time, however, Magdalen wasn’t speaking. For almost all of the time that they’ve spent together on those two days, there have also been two other people present, although, during that time, Wragge has sought to distract Mrs Lecount, so that she won’t hear any of the conversation between Noel and Magdalen.

To accept that, on the basis of the dealings that I’ve just described, Noel could now quickly be persuaded to propose marriage to Magdalen calls for a greater suspension of disbelief than I, for one, am able to achieve.

*****

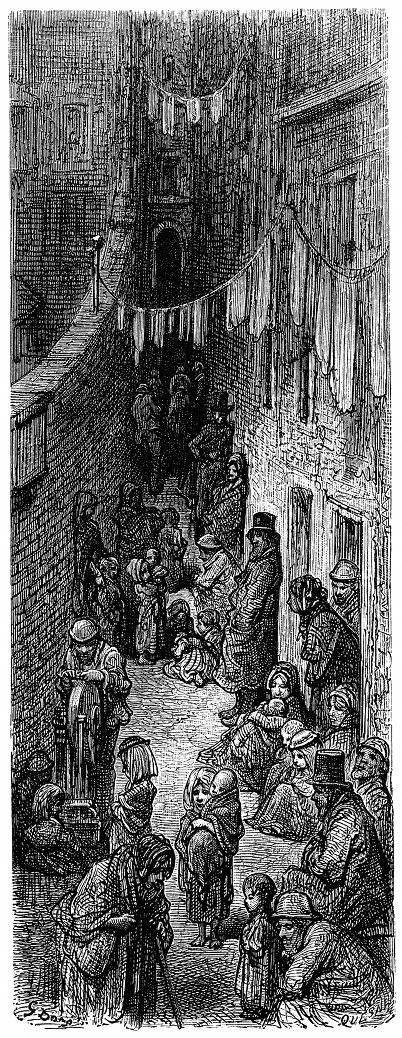

At about the date that our story has now reached, Drury Lane, London and its surrounding area were the scene of great poverty.

By way of confirmation, I mention that in the sketch entitled “Gin-Shops” in Sketches By Boz (1837), Dickens, having referred (here) to “Drury-Lane, Holborn, St Giles’s, Covent-garden, and Clare-market”, continues, “There is more of filth and squalid misery near those great thorough-fares than in any part of this mighty city.”

Further, in The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), Friedrich Engels describes (here) the dwellings in Drury Lane as “abominable” and writes, “In the immediate neighbourhood of Drury Lane Theatre [that is, the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane], the second in London, are some of the worst streets of the whole metropolis, Charles, King, and Park Streets, in which the houses are inhabited from cellar to garret exclusively by poor families.”

(The above 1872 drawing (from here) by Gustave Doré, depicts the inhabitants of Orange Court, Drury Lane. No very good reason appears to think that conditions in Orange Court were different from those in other parts of the Drury Lane area or were significantly worse by the date of the drawing than they’d been twenty-five years earlier.)

Poverty, however, wasn’t the only thing usually associated with the Drury Lane area in about 1847.

(The above print (from here) depicts a “woman of all trades” (a euphemism for a “female prostitute”) in the late eighteenth century. The woman depicted may have been from Drury Lane itself, since it constituted the eastern boundary of the Covent Garden area.)

Chapter 6 of Edward Walford, Old and New London (1890 edition) (here) is entitled “The Strand (Northern Tributaries)—Drury Lane and Clare Market”.

The chapter begins with two epigraphs:

“O may thy virtue guard thee through the roads | Of Drury’s mazy courts and dark abodes!”—Gay’s “Trivia”

“Paltry and proud as drabs in Drury Lane.”—Pope

(Although Walford doesn’t mention it, Gay’s “Trivia: Or, the Art of Walking the Streets of London” was published in 1716, while the line quoted from Pope appeared in his “Second Satire of Dr Donne”, published in 1735.)

In the body of the chapter, Walford, although without giving the name of the poem concerned or its date, quotes yet another poetic reference to the association of Drury Lane with prostitution, that of Goldsmith. He, like Pope, had referred to “the drabs … of Drury Lane”. (The poem is commonly called “Description of an Author’s Bedchamber” and is dated 1760.)

As well as quoting from eighteenth century poets about the association of Drury Lane with prostitution, Walford might have gone back earlier in time and quoted from the seventeenth century diarist Pepys (whom Walford does quote for other purposes related to Drury Lane). In a diary entry for MAR 21 1664/65, Pepys wrote (here), “In our way [to the Mewes] the coach drove through a lane by Drury Lane, where abundance of loose women stood at the doors, which, God forgive me, did put evil thoughts in me, but proceeded no further, blessed be God.”

In his most direct reference to the matter, Walford writes (I’ve added the bold emphasis and some bracketed publication information),

It will be remembered that in the Tatler (No. 46) [published in 1709] Steele gives a picture of the morality of Drury Lane, describing it as a district divided into particular “ladyships,” analogous to “lordships” in other parts, “over which matrons of known ability preside.” Its character, too, as well in the present as in the past century, is delicately hinted at by Gay, in the lines quoted from “Trivia,” at the head of this chapter. … [N]othing can confirm more clearly the character of the immediate neighbourhood, to which we have referred, than the fact that Drury Lane was the scene of the “Harlot’s Progress,” by Hogarth [published in 1732].

We thus see that for a period of over two hundred years, between 1664/65 (Pepys) and 1890 (the date of the relevant edition of Walford’s book), the Drury Lane area was usually associated with prostitution.

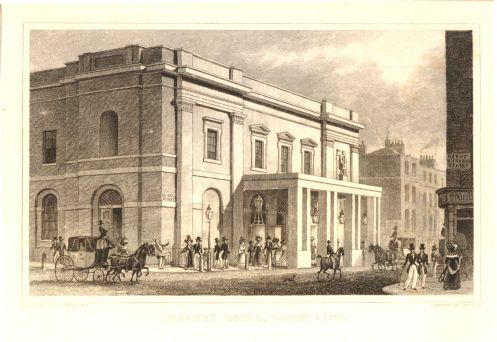

No doubt, the poverty with which Drury Lane was usually associated was a cause of the prostitution with which it was also usually associated. However, there was at least one other cause as well, mentioned incidentally in the passage from Engels quoted above. That was the presence in the area of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, which, in company with other similar places of entertainment, provided a ready source for prostitutes of moneyed clients.

(The above 1828 print, after Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, is © Trustees of the British Museum. It depicts the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane generally in the incarnation in which it presently remains (compare this present-day photograph). Note that Brydges Street is now called Catherine Street. Also, the street that’s depicted crossing Brydges Street isn’t called Great Russell Street, as appears at the right of the print, but Russell Street, Great Russell Street being a different street north of the Theatre Royal’s location.)

Coincidentally, by the year that our story has now reached, the problem of the London theatres as a catchment area for prostitution clients had become so great that the Lord Chamberlain forwarded a circular to metropolitan theatre managers, the manager of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane obviously being among them. That circular read (here), “The Lord Chamberlain having been informed that prostitutes are admitted without payment to some of the theatres and saloons open under the authority of his licence, his Lordship requires you to state in writing whether any such practice exists at the _____ Theatre.”

Whether the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane facilitated prostitution in the way described by the Lord Chamberlain, I can’t say, but, even if it didn’t, prostitutes still found the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane a lucrative source of business.

*****

After Captain Wragge has discovered that Noel’s been told by Mrs Lecount to check to see whether Magdalen has two moles on her neck, the following dialogue ensues between Wragge and Magdalen:

“I am going to give the lie direct to that she-devil Lecount by painting out your moles.”

“They can’t be painted out,” said Magdalen. “No colour will stop on them.”

“My colour will,” remarked Captain Wragge. “I have tried a variety of professions in my time—the profession of painting among the rest. Did you ever hear of such a thing as a Black Eye? I lived some months once in the neighbourhood of Drury Lane entirely on Black Eyes. My flesh-colour stood on bruises of all sorts, shades, and sizes, and it will stand, I promise you, on your moles.”

Who was it that suffered from those bruises around the eyes to which Wragge refers, which bruises were of all sorts, shades and sizes? Who was it that, suffering from such bruises, found it important to attempt to hide their presence? To me, the answer seems evident—at some unspecified time in the past, for some months, Wragge had been providing his painting service to prostitutes in the neighbourhood of Drury Lane, where he then lived.

When Wragge tells Magdalen that he “lived some months … entirely on Black Eyes”, what exactly does he mean? Does he mean that he was in the business of painting black eyes for money and that that business was sufficiently remunerative that he was able to live entirely on his earnings from it? Or since, as we know, Wragge isn’t exactly scrupulous about how he earns his living, is there any chance that he means instead that he lived entirely on the earnings of a woman or women with a black eye or eyes? In other words, does he mean that he had been living entirely on the earnings of a prostitute or prostitutes?

When, in an earlier weekly instalment, Collins described Wragge’s consideration of whether to assist Magdalen in her plot to trick Noel into marriage, he (Collins) had this to say about Wragge’s character:

A man of boundless audacity and resource, within his own mean limits; beyond those limits, the captain was as deferentially submissive to the majesty of the law as the most harmless man in existence; as cautious in looking after his own personal safety as the veriest coward that ever walked the earth.

That doesn’t sound to me like the description of a man who would be prepared to do what would or, at least, could be required in order to live on the earnings of a prostitute or prostitutes.

Incidentally, prostitution was the subject of two of Collins’s later novels, The New Magdalen (1873) and The Fallen Leaves (1879). One of the prostitutes who appears in the latter novel is beaten by her “protector” and bears bruising (although not on the face) as a result.

*****

Having hidden Magdalen’s moles from view, Wragge then invites Noel to look for them. According to Wragge, “The [alleged] moles supply us with what we scientific men call a Crucial Test.” Plainly what he means is that their presence or absence on an inspection of Magdalen by Noel will determine whether Mrs Lecount’s allegations about “Susan Bygrave” are all true or all false.

Wragge’s use of the term “Crucial Test” is surprising for more than one reason.

First, “we scientific men” don’t usually use the term “Crucial Test”; instead, for a reason that I’ll mention in a moment, “we scientific men” usually use the term (at least in English) “crucial experiment”. Secondly, if, as well as being scientific men, we are also classical men, as Wragge has earlier claimed to be, we probably wouldn’t be using the English term anyway; instead, we’d probably be using the Latin term “experimentum crucis”, used by Sir Isaac Newton (here) in 1671/72 to describe what was perhaps his most famous experiment, involving the use of two prisms. Newton used the term in a published letter containing his “New Theory about Light and Colors [written thus]”. (It was, of course, the Latin term used by Newton that led to the usual English term’s containing the word “experiment”, rather than the word “test”.)

I haven’t found sufficiently interesting to include in this post any representation of Newton performing his experimentum crucis. However, I have found a representation of an alleged discovery by Newton that so tickles my fancy that I simply can’t resist including it here.

The following 1827 painting by the Italian painter Pelagio Palagi (from here) is entitled “Newton’s Discovery of the Refraction of Light”.

The woman and child depicted have been said to represent Newton’s half-sister and her child. If the painting does indeed represent a half-sister of Newton’s, it must be his half-sister Hannah Barton, since his other half-sister was childless, while Hannah had two children, one of whom, Catherine, was said to be a favourite of Newton’s.

There’s only one little difficulty in the way of accepting Palagi’s charming domestic scene as accurate. While in his Opticks (1704), Newton does speak of experiments performed with soap bubbles, he says that the experimenter was himself and makes no reference to the involvement of anyone else, such as, for instance, his half-niece Catherine.

I was much taken by Joanne’s comment last time that Collins has put Noel Vanstone in the position of a serial reader, with something to read that he must wait for. Or really he has put him in our position: the actual serial readers didn’t have the next installment before them with instructions not to read it yet; that’s what we have done in this group. And let what happens to Noel Vanstone be a lesson to any of us who weakens and decides to read ahead.

I feel sorry for Noel in this episode, for the very first time, and this even though the narrator calls him a “miserable little creature.” His history of romantic humiliations, of always being scorned by attractive women, makes him seem sympathetic (to me at least), as does the knowledge that he is being lured into a trap that may end in his death — prompting Captain Wragge to say he wouldn’t be in his shoes for all his money.

I was struck in this episode by Collins invoking the “fatal force of circumstance”: has he referred to such a force in this way earlier in the novel? In other novels?

And the narrator talks of Miss Garth’s well-meant efforts. It’s an effort for me to think well of Miss Garth, but if the narrator tells me to, I suppose I must. He does note that the aforementioned fatal force does turn Miss G’s efforts awry: now for the second time, he says. Was the first time the publication of the handbill? Did that spur Magdalen on? This does.

The narrator seems to want us to fear that Magdalen will be driven to do something quite bad: marry and then murder Noel V. And I do fear this, but at least we can see the reluctance and unhappiness in Magdalen, letting us hope that her better nature will stay her hand. …

I also appreciated in Noel’s actions the dig at the reader who peeks ahead! Poor Noel – picking up on Leslie’s disbelief at this rushed proposal, I think it is best explained in the passage this week describing his previous (mis)fortunes with the ladies. On their first meeting Magdalen realises a financial approach will be useless with this miser, but in love he has no chance – the moment a pretty girl payd him attention he is lost.

The key theme of the week appears to be perception, or perspective. Yet again we are denied direct access to an important interview, forced to wait outside with Wragge while the proposal takes place. So too is Wragge denied sight of his niece the night before with the candles deliberately left unlit, just as Noel’s view of her is obscured by Wragge’s make-up skills. Noel attempts to obscure the truth and his appearance from Lecount but with less success. And then poor Mrs Wragge gets treated to a walk out with hubby, but again appearance and intention are at odds as he barks orders at her.

One question – Collins speaks of Miss Garth once again getting it wrong and pushing Magdalen away instead of bringing her back. I assume the first, unspecified occassion is the distribution of Magdalen’s description in York, which Wragge refers to when identifying Garth as the likely source of the description. Or is there another occassion that I’m forgetting?

Wow Leslie – your deduction that Wragge’s master painting/ colour mixing skills could come from his time as a pimp is really fascinating. Given that his assistance of Magdalen to sell herself in marriage is a similar kind of activity, I find this very persuasive. I was cheering for Wragge this week (as Sheldon reminded me earlier when I was put out by his misogyny, we don’t have to like the whole character to like the creation). I’m so glad that, thanks to Wragge’s skills and audacity, Magdalen isn’t (yet . . .) outed by her body.

Sheldon, why do you think we inching towards a murder plot? Would that mean that Magdalene would have to remain in the alias of Mrs NV, nee Bygrave, for the duration, in order to secure the inheritance? I didn’t think that would be sufficient vengeance.

I too had assumed murder on the cards, hence Wragge’s uncharacteristic desire not to want to know more, the implication being that Magdalen’s intentions after the marriage are too grisly even for Wraggr. I suppose it is possible that she plans simply to reveal herself (and not in the way Noel may be hoping for on their wedding night). But what would this achieve? Presumably her false name would render the marriage void and thus give her no claim to Noel’s fortune. If she’s hoping he’ll agree to a quiet divorce or division of wealth to avoid a scandal, then she may be in for a disappointment if she had underestimated how miserly he is. Moreover, such a plan relives the past, with Noel in the position of her father and Magdalen as his first wife, which yet again prompts us to question where our sympathies lie.

Hi Holly: Rereading, I can’t put my finger on any explicit description of a plan to murder Noel Vanstone, but towards the end of Chapter 1 of our current Scene, when Magdalen tells Wragge her new plan, which is to marry Noel, there are hints. (The August 2 installment, around p. 486.)

Wragge says, “And after the marriage–?”

Magdalen says: “After the marriage … I shall stand in no further need of your assistance.”

Wragge turns “deathly pale” and will have nothing to do with anything after the marriage. He becomes furtive and goes off to think about M’s plan. The first part, deceiving Noel into marriage, does not bother him and seems to him little different from past deceptions he’s practised, but in the prospect after the marriage he discerns “through the ominous darkness of the future, the lurking phantoms of Terror and Crime, and the black gulphs behind them of Ruin and Death.”

He worries about joining the conspiracy up to the point of the marriage; can he then withdraw without risk of being involved in “the consequences which his experience told him must certainly ensue”?

That’s what spoke murder to me.

You’re right that does sound more than a little foreboding . . . It’s strange how I’ve managed to skip over these bits – likely a form of wilful reading that doesn’t want to see the worst in our M! As Pete says, it’s a really interesting experiment in readerly sympathy.

@Holly: “Given that his assistance of Magdalen to sell herself in marriage is a similar kind of activity …” I see the trees; you see the forest!

@Pete: “Presumably her false name would render the marriage void …” I started to gather legal materials on this question a while ago, knowing that I’d have to write something about it at some stage. Happily for me, that stage hasn’t been reached yet, but I’ll just say now that we can’t be sure that the mere use of a false name by one of the parties to a marriage solemnised in 1847, the other party being ignorant of the falsity, would have allowed that other party to extricate himself from the marriage.